9 March 2023

The Retention Rubik’s cube

Author

Dr Russell Crawford

Director of Academic Innovation and Quality, Falmouth University

Retention is a worrying deficit model lurking at the dark side of the more palatable, student success driver that all HEIs must attend to as a priority. Whilst a loaded but necessary metric, retention is also one of the only descriptors that is equal parts adjective, noun and verb! Only in HE could we achieve that level of efficiency for a single word to cover so many things we all worry about.

The Office for Students defines retention as ‘the proportion of students who complete their programme of study and achieve their qualification’ which is, at least, logical but the gravity behind that simple statement is planet sized.

I’m quite focused on retention as a driver of institutional academic behaviour but prefer to come at it from a literature-informed perspective rather than a short-term year-on-year response that sees HEIs chasing our proverbial tails by ‘reading’ opaque variables and general themes and hoping they lead to a positive retention impact.

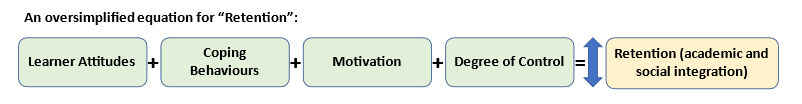

I can’t lay that position out and not qualify it with a killer theory to consolidate the point and my ‘Steer of the Year’ goes to Bean & Eaton’s Explanatory Theory of Student Retention. This work should be the gold standard when attempting to think about retention patterns because it takes a psychological lens to a host of intrinsically human factors that are key variables in ‘retention’, such as learning communities and tutoring provision, and positions them as being equally valid in a wider Retention Rubik’s cube (ah, the title makes sense now…sort of!). Very briefly, this theory proposes that ‘retention’ is the outcome of psychological interplay between learners’ attitudes, coping behaviours, motivations and degree of control they can exert over their environments (various) to collectively impact positively or negatively on academic and social integration into higher study and therefore, impact “retention”. As an equation, it might look like:

An interesting further point we can marry up with this theory is the sector’s reframing - post-pandemic - of well-being in higher study. Ideas that have been around for decades are enjoying new relevance (healthy curriculum design, anyone?) and in some cases, a new veneer (cost of living nationally eclipsing a lively historical cost of learning debate) all with the added pressure of business-critical costs rising, more diverse students coming into higher study and our duty of care to see them all through it.

Looking at retention though a lens of well-being opens up its interpretation to a host of real-world factors that are hidden within the broad umbrella used to keep track of why students leave university study.

It’s not atypical to see a large proportion (can be up to two thirds in some HEIs) citing ’health’ or ‘mental health’ as their reason for leaving, but under that sits a myriad of drivers and therefore, questions, that Bean and Eaton’s theory brings to the fore:

Learners’ attitudes - are they on the right course in the first place and are we confident enough in that to be sure? Are they engaging with the academic challenges of their course, or indeed, engaging more broadly with the learning communities we spend so much time establishing for them?

Coping behaviours - are learners getting the Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA) and learning support they need and are entitled to in a timely manner? Are learners actively seeking support from the infrastructure before leaving becomes the best option and who is monitoring that?

Motivations - are learners taking ownership of their time management and pace of learning? Are we designing ‘healthy’ curricula well enough that it is accounting for peaks and troughs in study intensity that may manifest under a ‘health/mental health’ reason?

Degree of control - are we treating all learners as adults, projecting and supporting a sense of agency and, critically, building our policy environments the same way? Are we empowering learners enough to be able to use that agency to mitigate some of the challenges raised here?

It’s easy to sit and pontificate on this, but to convince you that it’s more than talking the talk, last year (which seems like a lifetime ago in wibbly wobbly HE time), colleagues and I created and evaluated what we call The Social Induction Framework (developed through a Collaborative Enhancement Project funded by QAA Membership) and the themes from Bean and Eaton were very much evident in how we hoped students and staff engaged with our Framework.

While it is early days in terms of longitudinal reflection on it, we believe that when applied well our Framework can facilitate on-boarding of learners in a way that supports both academic and social integration precisely because they are essentially one and the same within that critical first week of higher study. What the Social Induction Framework managed to capture was the idea that those very first interactions during on-boarding were malleable to design; to have a framework establish positive attitudes, empower ownership in engaging help where needed, learning to cope and relish joining new learning communities, scene-setting motivation for the next years of study and finally, taking control of their lives, their learning and their future.

Back to the idea that retention is a complex, multi-faceted, ever-changing driver that is some sort of approximate read-out of student success, when we have the latitude to build our curricula with compassion and awareness of the cognitive and social load on learners joining us, we are in a much better position to at least arrange all the colours on a few sides of that cube. Right?