Project Blog: January 2026

Assessing assessment: exploring the link between design and awarding gaps in Higher Education

Author: Gabriella Cagliesi SFHEA, Professor of Economics , University of Sussex Business School

Despite decades of reform and research, ethnic awarding gaps remain a persistent challenge in UK higher education. While much attention has focused on curriculum and support services, our new cross-university study highlights a crucial but often overlooked driver: assessment design.

The pandemic disrupted learning in profound ways, but it also created unintentional natural experimental conditions, offering a unique opportunity to examine how changes in assessment and institutional policies impacted awarding gaps.

Using quantitative and qualitative data from the University of Sussex (UoS), Queen Mary University of London (QMUL), and University College London (UCL), we investigated how different assessment formats influenced student performance across diverse backgrounds, as well as their preferences and attitudes toward module choices.

The problem is not simply that awarding gaps persist, but that they appear to be systematically shaped by how we design assessment. While curriculum reform and student support have received sustained attention, assessment design is often treated as neutral or technical. Our study challenges this assumption by showing that changes in assessment format can widen, narrow, or even eliminate awarding gaps.

Awarding gaps and institutional data

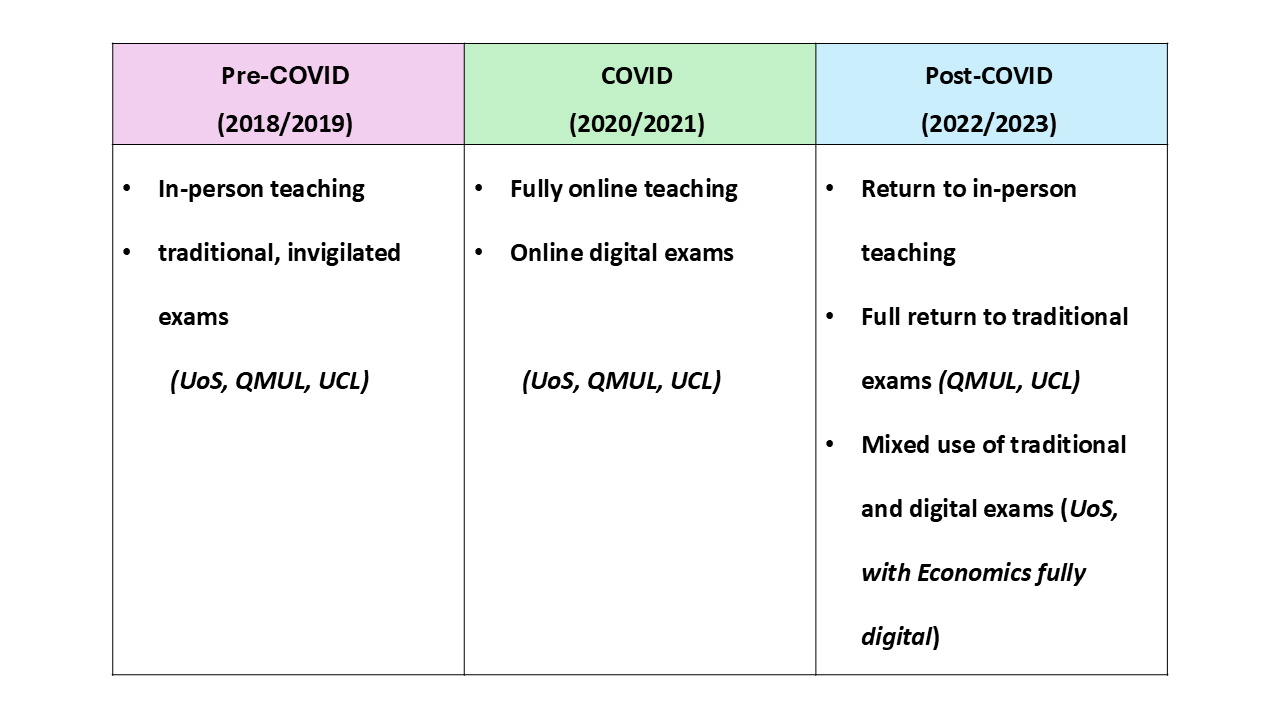

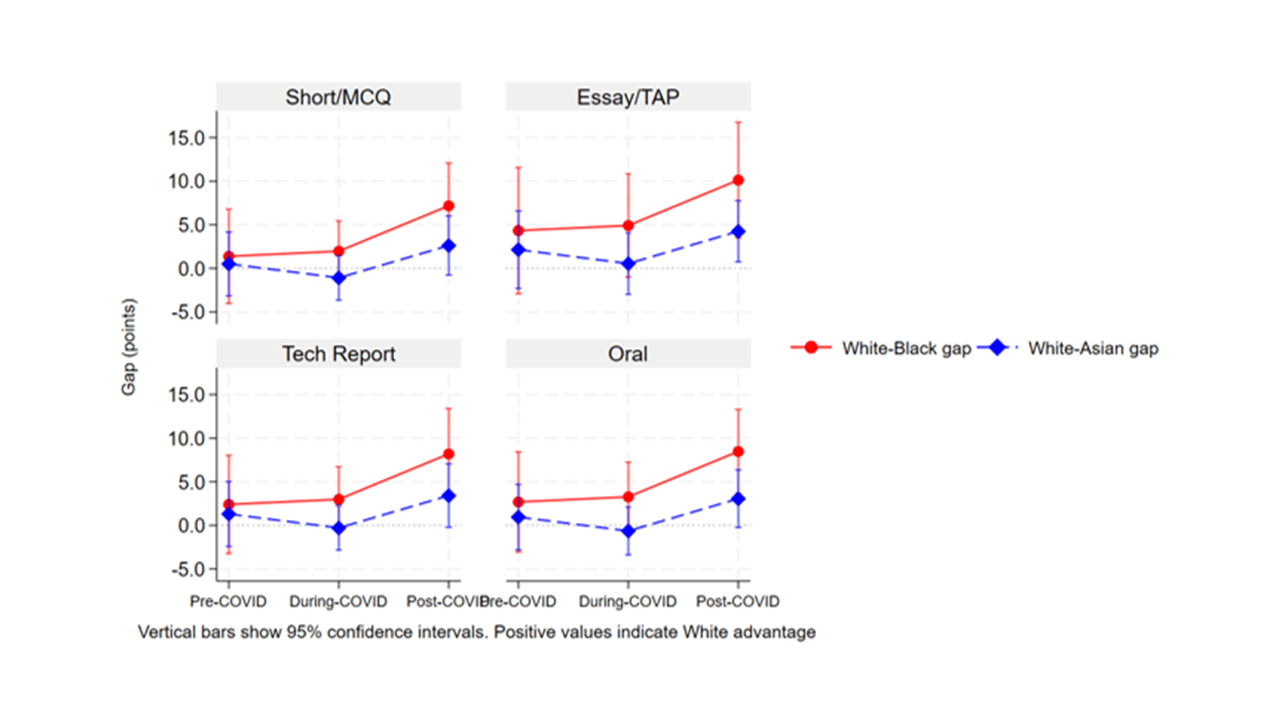

We examined student outcomes across three academic periods, each characterised by distinct modes of teaching and assessment. This allowed us to explore how changes in assessment design relate to patterns in student attainment, while controlling for key student and academic characteristics.

We looked at a range of departments and degree programmes and paid particular attention to single-honours Economics, where available, as its consistent content across institutions provides a useful lens for comparing student outcomes when assessment formats differ.

Three key findings from the data

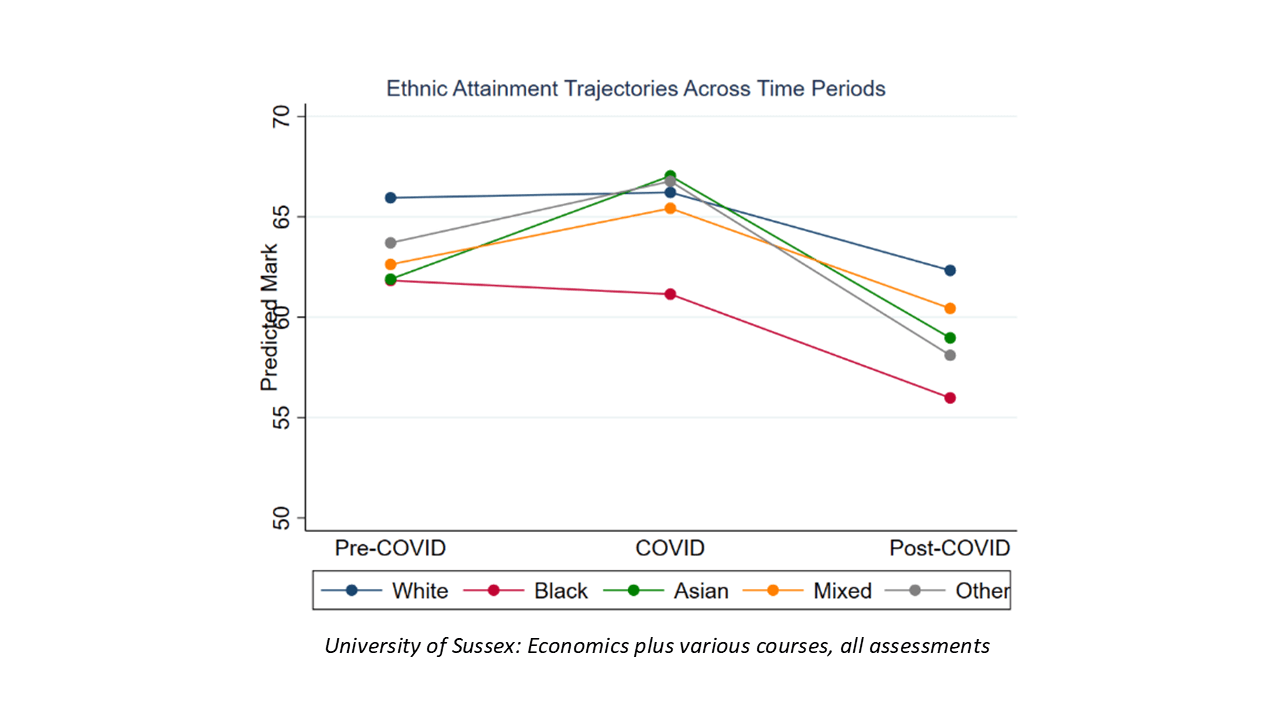

1. Awarding gaps narrowing or disappearing during the pandemic:

When universities adapted to structured digital formats, ethnic awarding gaps narrowed significantly:

What worked?

More coursework and fewer final exams (especially fewer high-stake exams). Structured online formats, such as open-book assessments, replaced high-pressure formats.

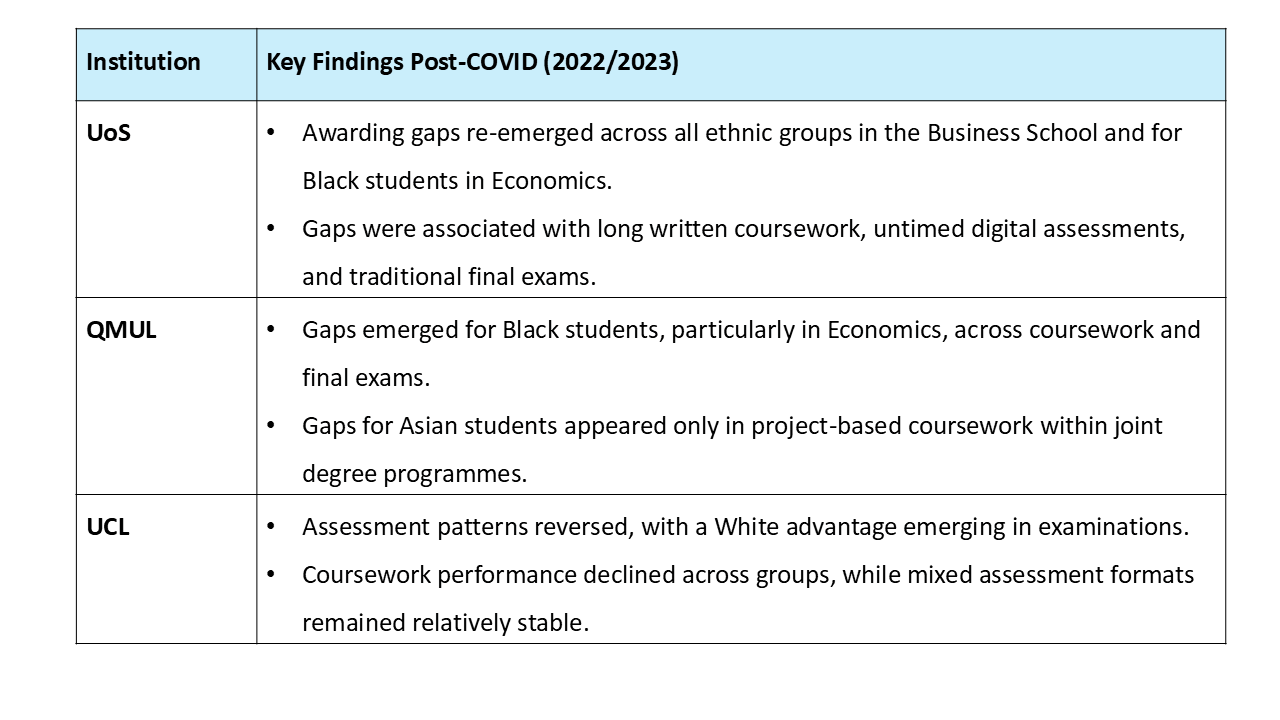

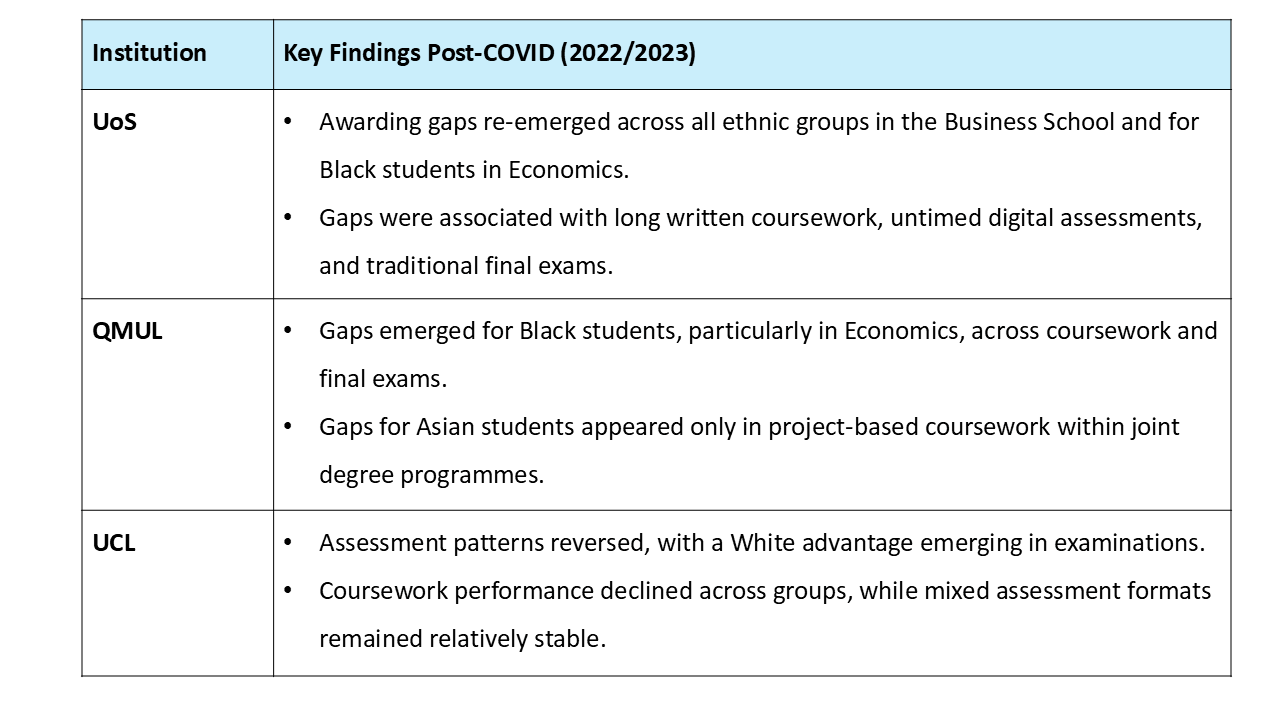

2. Awarding gaps re-emerging or widening post-COVID

As teaching and assessment practices reverted to pre-COVID formats, awarding gaps began to re-emerge.

What might this suggest?

Structural barriers may have been temporarily lowered under more structured, less pressured assessment regimes. Post-COVID, students may have faced greater difficulty re-engaging, or may have been unprepared for the return to high-stakes formats.

3. Assessment format matters

Across institutions, extended and open-ended assessment formats (such as essays, reports, and untimed-long digital exams) were associated with larger awarding gaps in the post-COVID period. In contrast, shorter and timed assessments were associated with smaller or no gaps.

Final examinations were particularly challenging when they carried high weighting and required strong self-regulation, with these formats more strongly associated with the re-emergence of awarding gaps.

One of the clearest findings from the institutional data is that assessment design plays a key role in shaping awarding gaps. Notably, the re-emergence of gaps was not confined to a return to traditional exams, but was also observed and in contexts where digital assessment formats remained in place.

Beyond ethnicity: Intersectional Insights

Beyond ethnicity, performance is also shaped by other intersecting factors. Mental health–related disabilities were associated with sustained attainment penalties. Socioeconomic disadvantage also shifted in important ways: at Sussex, post-COVID penalties became concentrated among male students from low-income backgrounds, reversing pre-pandemic gender patterns.

Quantitative modules also tended to disadvantage students, particularly in final examinations. An exception emerged at QMUL, where Asian students demonstrated stronger performance than other groups.

From data to voices: listening to students’ experiences and views

Alongside the institutional data, we listened to students from a range of disciplines and stages of study. While most enrolled after the pandemic, their reflections—presented in the excerpts below—provide insight into how assessment design shapes decision-making, perceived pressure, confidence, and engagement, offering important context for understanding students’ learning experiences and, ultimately, their performance.

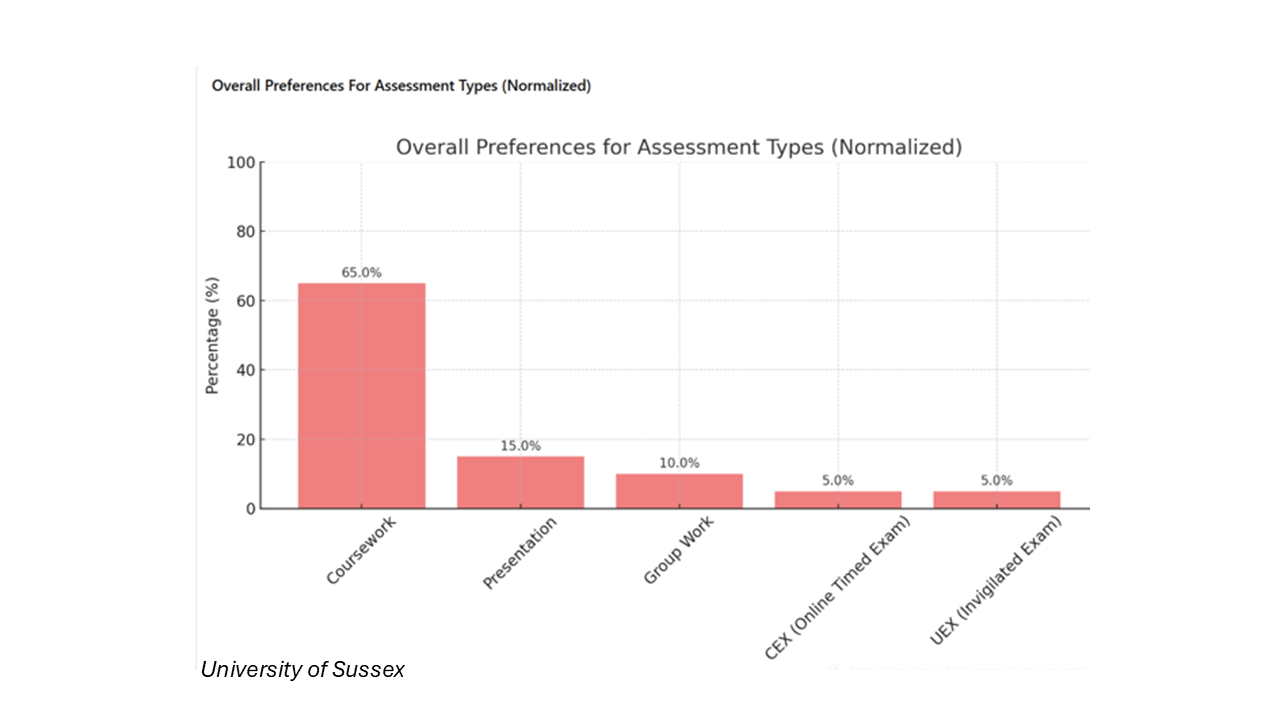

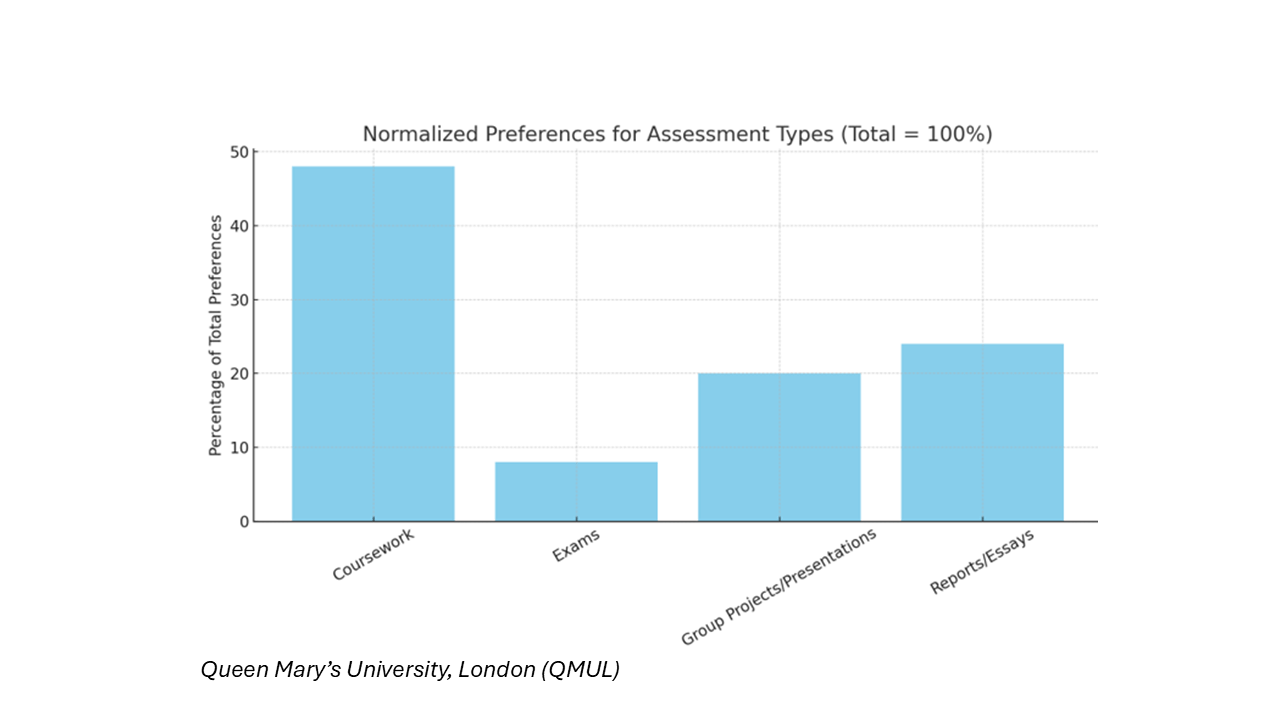

What students prefer

"I prefer coursework because you get to build up over time and you don’t have to do it in a time-constrained way." (UoS)

“I actually prefer group work… because in the real world you have to work with other people.” (UoS) On the other hand, students at UCL tend to have a preference for individual assignments.

“ I like to have a balance between some group work and some individual ones.” (UoS)

“When I'm in my room doing my exam, it's just more calm… you can display your full knowledge more easily.” (UoS)

“Coursework felt more connected to real-world skills and allowed me to show what I actually understood, rather than what I could recall under stress.” (QMUL)

Preference for: “gradual and formative assessment formats” linking these with more sustainable learning and opportunities for reflection. (QMUL)

Interpretative cue: Overall, students tend to value assessment designs and conditions that prioritise process, authenticity, and manageable pacing, and that allow them to demonstrate their knowledge effectively without excessive time pressure.

How preferences affect choices

“When I was choosing my modules, I was looking at the assessment modes” ; “I try to steer away from essays and go more for take-away papers”; “I don’t really see the point of doing exams if I can avoid it.”(UoS)

“If I find someone not really passionate into it, I feel like I won’t choose that module. Testimonials from previous students really influence us.” (UoS)

“I chose a module because it was 100% coursework to avoid exams, but I didn’t realise how heavy the workload would be.” (UCL)

Institutional insight (UCL): Students reported making strategic module choices based on assessment method, perceived difficulty, and career alignment. Some described actively seeking information on historical performance patterns to inform these decisions, while also noting frustration with capacity limits and rigid selection systems.

Interpretative cue: Assessment preferences translate directly into strategic choices. However, these decisions are often made under conditions of imperfect information, meaning that attempts to reduce perceived risk can sometimes lead to unintended consequences, such as workload concentration.

Where students encounter barriers

“If there's just one piece of assessment, there's just too much pressure on the day”; “Another concern about 100% is that you don’t really get any feedback… once you’re done, you’re done"; “I’m more for at least two assessments because I think I just put too much pressure on one final assessment" (UoS)

“If you're going to stick to in-person assessment, you should build it from year one and continue to year two and three.” (UoS)

“Some of the exams don’t even have marking criteria”; “Sometimes with essays you think, am I going in the right direction? Sometimes the quite open-ended essays… you can write a whole essay and then think, am I going down a completely wrong path here?” (UoS)

“I don’t really like when group work is worth 70% of your grade… I can’t understand why my grade could rely on people that don’t care about the subject.” (UoS).

UCL students expressed negative reactions to group work projects because of issues such as difficulties in work allocation in large groups, lack of commitment from some team members, and concerns about fairness in grading when participation is uneven.

“Maths can swamp you… if you miss one step, everything folds”; “There was a massive gap between the people that had done A-level maths and the people that hadn’t”; “I think there could be more support because it can be quite daunting”; “I knew there was help, but I didn’t really know how to access it” (UoS)

“I don’t really know what to do when I get stuck. Sometimes I just leave it and come back later.” (QMUL)

Institutional insights UCL: Some students reported choosing modules with 100% coursework to avoid exams, but later regretted this decision due to overassessment or unexpectedly high workload. Students also highlighted rigid module structures and capacity limits that constrained informed choice. Students described difficulty adjusting to programming- and maths-heavy modules, particularly when transitions from qualitative content occurred rapidly and without sufficient scaffolding.

Interpretative cue: Concerns centre on high-stakes assessments with unclear expectations and marking criteria, alongside limited opportunities for preparation and feedback. Barriers are amplified in group-based and quantitative assessments when grading practices lack transparency or when progression into more technical content is insufficiently scaffolded. These patterns point to structural, rather than individual, sources of difficulty and reinforce the need for diversified assessment portfolios, clearer marking guidance, and progressive preparation across programmes.

One of the clearest findings from the focus groups is that students have clear views on what they value and how assessment design shapes their performance. They often make strategic decisions about module choice, influenced not only by content or interest but also by the form and structure of assessments.

* Methodological note: These insights are based on a limited number of focus groups and are intended to be illustrative rather than representative.

What should change?

Data and student voices suggest clear, actionable steps:

- Diversify assessment portfolios: mix structured, time-limited tasks with authentic, process-driven work.

- Avoid high-stakes assessments, especially in final modules.

- Design for inclusion: scaffold tasks, clarify expectations, support self-regulation.

- Provide thoroughness in instruction and consistent marking guidance.

- Offer greater flexibility and clearer, more comprehensive information during module selection.

Conclusion: mind the design to mend the gap:

- Awarding gaps are not inevitable. They are shaped by how we design assessments. Our data shows that gaps can emerge, disappear, or re-emerge based on design.

- As AI and new technologies reshape education, we have a chance to rethink assessment for both integrity and equity. AI tools should be seen not just as threats to integrity but as supports for learning and engagement.

What’s next?

We’re continuing to analyse focus group insights and collaborating with academic departments to put findings into practice. On 8 December 2025, we presented our preliminary results at the QAA‑funded Awarding Gaps and Assessments Conference, hosted by the School of Economics and Finance at Queen Mary University of London. Conference: Programme

The conference provided an opportunity to share early findings, gather feedback from colleagues across institutions, and discuss how assessment design can better support equity in the years ahead. Video Conference Awarding Gaps and Assessments