An evidence-based toolkit on leveraging Generative AI to support the graduates of the future

Introduction

Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) offers significant opportunities to higher education, providing a unique opportunity for universities to recalibrate educational activities to deliver graduates with the skills to address future global problems. However in order to take advantage of this opportunity Universities need to complete some essential groundwork to create the optimal environment to facilitate appropriate and effective engagement with generative AI.

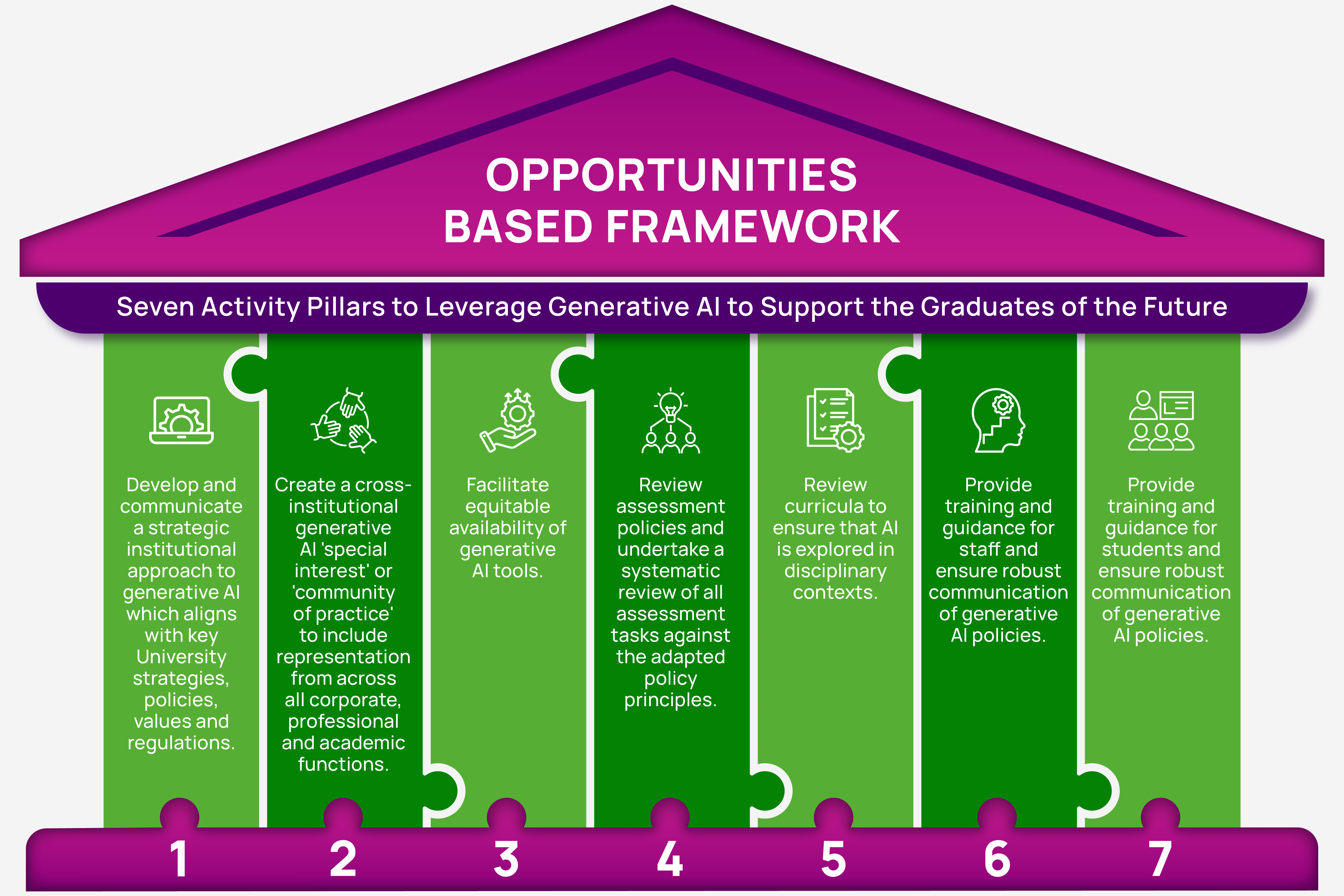

This toolkit identifies the baseline actions that higher education institutions must take to ensure that they have the capabilities and infrastructure to harness the potential of generative AI to support students learning and develop their higher skills for life after graduation. It outlines seven key pillars of activity that institutions should complete to maximise the benefits, whilst maintaining legitimacy as educational institutions delivering valid and robust academic awards. The toolkit also offers a bank of case-studies from a variety of disciplinary contexts which showcase how our partners universities are addressing the seven pillars of activity.

This project focuses on learning, teaching and assessment. However, it acknowledges that Generative AI will transform many aspects of the higher education sector including research and the wider technical and administrative operations of universities.

Grounding principles

- Higher education must engage critically and ethically with generative AI, directed by human-centred principles (including compassion and empathy).

- Universities must enable access to a range of licensed AI tools and technologies for use by both their staff and students.

- University curricula in all disciplines must evolve to accommodate (and in some cases drive) developments in generative AI, with appropriate resource allocated.

- AI literacies are a universal graduate attribute which must be effectively supported and integrated in all University curricula.

- Generative AI poses significant challenges to the integrity of academic awards in higher education.

- Higher education assessment policies and strategies must change in line with developments in generative AI.

- Learning and teaching practices must evolve to support changes to assessment strategies.

- Universities must fully support their staff to develop their disciplinary curricula and learning, teaching and assessment strategies in line with developments in generative AI.

- Effective approaches to generative AI will require universities to work across their multiple functions and in partnership with students.

The obvious caveat is the speed of developments in generative AI. This toolkit presents a moment in time and outlines immediate activities fundamental to addressing the challenges and leveraging the opportunities of generative AI.

The challenges of AI

Generative AI is unlocking challenging questions about the purpose of higher education.

It is compelling universities to confront the question of what is ‘higher’ about higher education beyond its linear progression from the compulsory education sector.

Most universities define a graduate skills-set which encapsulates a holistic view of the outcomes their graduates will be able to demonstrate, often described as graduate attributes. These commonly include academic skills such as creativity, problem solving and analytics and critical thinking, human-centred skills such as adaptability, team working and collaboration, resilience and self-awareness and technical skills such as digital competencies.

However, academic curricula and assessment has, by and large, focussed on subject knowledge and skills and not the explicit development and assessment of these graduate attributes. The obvious question is how universities are actively, and intentionally, developing these skills in their graduates through their subject-focused curricula.

Vocational and technical disciplines which are preparing students for specific graduate careers have more robust responses to these questions. However, the challenge remains for academic disciplines more broadly to articulate how they are developing, and assessing, higher graduate skills.

Now that generative AI can perform… [lower order] functions for us, we can accelerate the trajectory of learning and assessment to focus on developing future skills, transferable graduate skills such as problem-solving abilities, building students' capacities for critical thinking, self-awareness and collaborative work, to name but a few. This renewed focus on what we might see as the core values of learning should surely be seen as a positive thing.

Hughes and Linsey (2025) How AI may make us rethink the purpose of HE, QAA Blog.

Questions about the development of higher graduate skills are compounded by the fact that assessment in higher education has, for the most part, privileged the written word, valorising academic writing. With developments in generative AI, academic writing has become more easily accessible and therefore can be afforded a lower skill level. The intellectual argument remains sacrosanct, but (academic) writing becomes ostensibly obsolete as a measure of intellectual excellence. We argue this in our project blog:

If machine ‘intelligence’ can write an essay in an academic style or a report in a corporate voice identikit in terms of expression and tone, then why should we value, recognise and reward that ability as a higher skill?... When we have AI to do it for us, it appears it's no longer something we need to be able to do for ourselves.

Hughes and Linsey (2025) How AI may make us rethink the purpose of HE, QAA Blog.

These challenges must prompt a more explicit drive to define and assess the skills, as well as the knowledge, being developed in modules and courses, ensuring that these are effectively translated into the assessment criteria.

The question becomes ‘Is this assessment authentic and does it build the skills that are required in an Al enabled world?'

How does AI support graduates of the future- an update on project progress

A critical consideration of what is ‘higher’ about higher education inevitably leads us to question our ‘quality’ measures in the higher education sector. Generative AI is already challenging the appropriateness of some of our current quality frameworks. For example, the English Higher Education regulator, the Office for Students, expects providers to assess spelling, punctuation and grammar to “ensure the quality of students’ education” (OfS, 2021).

However, if Generative AI can deliver in this space, how can we argue that this is a ‘higher skill’ that needs to be assured?

Perhaps the most hotly debated challenge of Generative AI in the higher education sector is how universities ensure their graduates have gained the pre-requisite knowledge and skills required for their conferred degrees, and the authenticity of students’ work.

One of the first actions that our institutions took after the public launch of Chat GPT in November 2022 was to secure academic integrity by identifying the submission of unacknowledged AI generated content as plagiarism or commissioning and providing guidance to students on how to avoid breaches of academic integrity.

However, generative AI remains a significant threat to the integrity of university degrees. Universities cannot console themselves that AI generated assessments are not rigorous enough to pass. There is growing evidence that AI- generated submissions are going undetected and the grades that they are being awarded are gaining higher marks than those achieved by real students. Whilst higher education must critically engage with Generative AI, universities must also find ways to secure their assessment to ensure that students have met their programme learning outcomes.

The resilience of assessment has been a key focus for our universities. Partners have begun to rethink assessment, some creating explicit tools to help staff stress test their assessments. As Generative AI technologies evolve, initial workarounds are becoming less reliable, and many types of assessments will present a low barrier to misuse.

As a result, we argue that the most sustainable approach will be to focus on authentic assessment principles where students are disincentivised to use AI as a tool to ‘do’ their assessment but are supported to use it effectively and appropriately (where it is integral to the assessment), with a greater emphasis on the process of completing the assessment and the skills set that this requires.

The opportunities Generative AI offers to higher education and the graduates of the future.

Debates around the use of generative AI has inevitably focused on detection, whether with the assistance of a detection software or not. Whilst there are differing attitudes to detection software there is a universal recognition of the challenge of hybrid writing where standard tools used by students, and sanctioned by our institutions, have AI embedded within them.

Generative AI creates significant epistemological challenges in terms of how knowledge is both created, circulated and validated.

Growing evidence supports the view that using generative AI to create outputs lessens the impact of human agency on epistemic development and creates what Sarkar (2024) defines as “mechanised convergence” where users have a strong tendency to accept AI output without critical judgement. The danger here, also discussed in more detail in challenge 5, is that knowledge circulated and validated becomes homogenised, reflecting dominant narratives and discourses, and threatening to negate multiple perspectives.

Generative AI can certainly empower…But by embracing this writing tool are we continuing to accelerate the tendency for a digitally determined realm of discursive homogeneity? Might we be making all those diverse voices start to sound the same – and even to say the same things?

Hughes and Linsey (2025) How AI may make us rethink the purpose of HE, QAA Blog

Perhaps more worrying is that users of generative AI are not aware of this dangerous predisposition. This is also the case in the field of education where, without guidance and support, students are using AI outputs without the required critical engagement.

Discussions with students in our own institutions have found that a significant number of students are not aware of how often Generative AI systems produce inaccurate or made-up facts, statistics or citations, produce biased outputs…Added to this is the lack of understanding by students (and staff) on how digital media of all types can be generated, and potentially manipulated by AI, underlining more than ever the critical and evaluative skills that are needed to work in the digital world.

There is also growing evidence of significant cognitive implications of regular use of generative AI, where it exacerbates cognitive ‘atrophy’ or ‘offloading’, reducing the capacity for critical thinking and reflection. This is hugely significant for high education as these are exactly the graduate skills that we claim to develop in our students.

In addition, recent work has revealed that, used for the purposes of ideation, generative AI can actually constrain creativity and ‘outside the box’ thinking, with the current configurations of AI tools being incompatible with encouraging truly original ideas (Anderson et. al., 2024).

As generative AI tools become increasingly integrated into education University must foster environments that balance the benefits of AI with the development of higher cognitive skills enhancing, rather than diminishing, key graduate skills such as creativity, critical thinking and problem solving.

Perhaps one of the most fundamental threats from Generative AI is its impact on the trust relationships between universities and their students, and between students themselves.

The core of the issue lies is the fact that students are rapidly embracing generative AI for its perceived benefits in efficiency and work quality, while universities are struggling to keep pace with their approaches and polices. The concern here is that a vacuum is created, where both students and educators are uncertain as to what is acceptable use of generative AI and what is not.

Within this vacuum, a "trust deficit" has the potential to propagate, where students are expressing apprehension about the fairness and clarity of institutional guidelines, and educators become suspicious of the intentions of students whilst grappling with the pedagogical and ethical implications of AI in the classroom. As we navigate the AI enabled future, we must build a foundation of trust through transparency, collaboration, and clear guidance.

All our partners have acknowledged the central role that continual dialogue is playing in understanding how students are engaging with generative AI and their key concerns. Students’ AI literacies are clearly wide ranging, but many students remain extremely anxious about its (mis)use and about ‘getting it wrong’… These concerns necessarily need to feed into our strategic approaches to generative AI.

Students need to be supported to understand the limitations of generative AI and recognise that whilst its use may be expedient and appropriate in some settings, educational settings require a level of criticality and authenticity not supported by, or delivered through, these tools.

Ensuring that our students know and understand our institutional guidance on Generative AI is a key priority for all partners, but we recognise that students are starting to challenge the efficacy and authenticity of policies and guidance as they increasingly use these tools in their own environments and perceive how they are being used in broader society.

Compounding these issues of trust, students (and staff) are also beginning to question and challenge their institution’s position to generative AI as it pertains to the protection of (their) intellectual property, environmental sustainability and broader issues of equity and fairness.

Generative AI is a powerful mirror reflecting the values, priorities, and biases of our societies, as far as they are represented across the global web.

The uncritical pursuit of AI-driven productivity and automation poses a grave and multifaceted threat to the core principles of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, principles that higher education claim to hold up. Dangers include embedding systemic bias into admissions, new and more complex digital divides, and the hyper-homogenization of knowledge.

By virtue of the data on which they are trained, generative AI outputs are known to lack representation from women and people of colour. They also have a “language problem” performing poorly in non-English languages and are geographical challenged with knowledge created in whole continents being severely under or misrepresented.

As a result, the exponential growth of Generative AI has the potential to reverse the progress made by high profile campaigns in global higher education which call for epistemic diversity through decolonising our higher education curricula and (re)valuing indigenous and local knowledge systems.

However, with this challenge, comes an opportunity to reopen key debates about how to more effectively capture diverse knowledges through higher education curricula and pedagogy, addressing the destruction of other valid ways of knowing and understanding the world.

One obvious opportunity is the challenge that generative AI is placing on text-based assessment. A move away from text-based assessment will require universities to embrace more diverse modes of assessment which, in turn, will encourage the development of other skills in students such as oracy, supported through a move to more dialogic learning and teaching. In turn, this could open up ways to (re)value the authentic voices of our students, supporting neuro-diversities and access to higher education for students with less formal qualifications.

Academic writing has been privileged over other forms of writing and viewed as more legitimate than different forms of expression, including oral traditions. However, the ability to write academically has for centuries been limited to a small group of people – academics themselves and others with access to that educational privilege and cultural capital (very often those whose parents and grandparents also enjoyed the benefits of university educations)…if generative AI leads to the diminished value of the art of academic writing, it may open the door to, and restore, our understanding of the importance of dialogue, of dialogic and dynamic processes of teaching, learning and assessment which empower the diversity and distinctiveness of individual voices and the interrelation of those voices.

Hughes and Linsey (2025) How AI may make us rethink the purpose of HE, QAA Blog.

Whilst Generative AI has the potential to ‘level-up’, whether through embracing alternative forms of assessment, democratising academic writing or creating AI tutor tools which support students who feel marginalised in the academic system, knee jerk reactions need to be avoided that may reverse progress made in the inclusivity realm. Amongst others, these reactions may include a wholesale return to closed book examinations or abandoning anonymous marking. The impact of these changes across our diverse student communities needs to be carefully considered.

One of the key challenges for universities is how to embrace generative AI whilst mitigating the ethical risks which include issues of control, equity, environmental sustainability and the ethical implications in the global distribution of labour in the AI industry (see for example, Muldoon et. al, 2024).

There are several complex copyright issues related to the development and use of generative AI tools, most pressingly that Generative AI tools are being trained on published and unpublished material with little regard for the copyright of the original content creators. This is being compounded by the fact that there is currently unclear statutory copyright protection of AI-generated outputs.

For example, in the UK there is copyright protection for purely computer-generated works, but the UK Government have argued in their ‘Consultation on Copyright and Artificial Intelligence’ that “it is not clear that this protection is widely used, or that it functions properly within the broader copyright framework” (UK Government, 2024). Writers, artists and musicians, amongst other creatives, are becoming increasingly vocal about the implications of AI and copyright for the ownership of their artistry.

Furthermore, the environmental impact of generative AI has been widely debated. Whilst its impact is undoubtedly complex and as not fully tested, we do know that is consumes a significant amount of energy and water, which is particularly impactful on a regional scale, and creates large amounts of carbon emissions. Inevitably the global’ price of knowledge creation will have significant and differentiated local impacts and no doubt will fall on the most vulnerable communities.

Whilst it remains very difficult to get accurate data on the environmental impacts of Generative AI (Crawford, 2024), there are a growing number of case-studies about how its exponential growth has placed already vulnerable communities in increasingly perilous situations.

QAA Project Blog (2024) The opportunities Generative AI offers to higher education and the graduates of the future.

Whilst still embryonic, we are seeing a growing backlash by both staff and students against the use of generative AI.

…we are beginning to see a backlash by both staff and students who are choosing not to use this technology, based on ethical concerns including bias, environmental impacts, and the infringement of intellectual property.

Currently, this opposition is relatively discipline specific, with students studying creative subjects allied to music, creative writing, design and art particularly unsettled about the implications of AI technologies for their industries and graduate prospects. However, there is no reason to suspect that this backlash will diminish in the foreseeable future.

Whilst the big picture solutions are beyond the bounds of individual institutions and indeed the sector more broadly, universities must ensure that they support students to understand these ethical dilemmas. In many cases, students are still unaware that the content they are inputting into commercial AI platforms through prompts or uploads, may grant the tool the right to reuse and distribute this content, and/or may breach copyright and/ or their privacy.

It is incumbent on all universities to ensure that their staff and students know and understand what Generative AI is, and what it isn’t, what it can and cannot do, and fundamentally that no matter how ‘clever’ these tools seem, they are not intelligent in the human sense. This understanding can help to define the higher-order skills that generative AI cannot deliver.

As with the other challenges identified here, there is an equal opportunity for higher education educators to address social justice and sustainable futures in their programme syllabi, as they relate to AI, further supporting their long-standing commitment to both the protection of intellectual property and environmental sustainability. However, universities will need to tread a fine line between ensuring that students are prepared to work in an AI enabled world, whilst defending the key ethical dilemmas raised by AI more broadly.

The final challenge identified in this project is around embracing ‘big tech’.

Whilst, it is not solely related to generative AI, it has certainly been crystallised by it. For some time, Global IT companies have been consolidating their place in the digital ecosystems of higher education with the widespread use of cloud based digital infrastructure – both hardware and software.

For the most part, this tech has not been created explicitly for education and universities are having to acknowledge and mitigate against the challenges of using this technology for educational purposes.

Updates are being made to these technologies without due consideration to the academic cycle which can make it challenging to embed generative AI tools into learning, teaching and assessment, if features are being changed, updated, or withdrawn with little or no warning.

One major point of tension is between the narratives deployed by the ‘big tech’ companies around the efficiency and productivity gains of generative AI tools, and Universities’ educational mission to develop the skills of criticality and creative engagement in their students.

Whilst not innately incompatible, the high-level messaging of the tech companies can be problematic and directly contradict academic policies on academic integrity, as well as the quality of educational knowledge and the development of key higher order skills.

Other challenges include those related to continuity and digital equity. Companies may offer deals to students directly offering enhanced capabilities and privacy protection for time limited periods or offer free access to advanced tools again for a limited time while the tools are in beta release.

Students can use personal free accounts (including options not to login) or subscribe to access more capabilities, with two paid subscription tiers now commonly available.

In addition, some of the more powerful specialist tools and capabilities that are available such as the research assistance tools have access to pay walled journals – creating inequity between those who can pay and those that cannot.

It is therefore essential that universities continue to monitor generative AI tools and platforms as they evolve and new capabilities are released, and assess the ongoing implications for learning, teaching and assessment.

It will be necessary to maintain universal access to licenced tools as our university communities engage with many different activities demanding enhanced assurance around data (such as creating feedback on student work, use in administration activities, use in open classroom situations).

However, these tools should not necessarily be regarded as fixed over time and it may be beneficial, within financial constraints, to consider the mix and range of tools available to students and staff, importantly including assessing specialist tools developed specifically for education and research, such as virtual learning environments integrated chatbots and research assistant tools, which may or may not be generative AI.

In doing this though we need to be purposeful and carefully assess the impact, particularly the impact on student learning. What we do know for certain is that the range and capabilities of generative AI tools will rapidly evolve moving forward.

Anderson, B.R., Shah, J.H. and Kreminski, M., 2024, June. Homogenization effects of large language models on human creative ideation. In Proceedings of the 16th conference on creativity & cognition (pp. 413-425) https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.01536

Muldoon, J., Graham, M. and Cant, C. (2024) Feeding the Machine: The Hidden Human Labour Powering AI. Canongate Books.

Sarkar, A. Xu, X. Toronto, N. Drosos, I, Poelitz, C. (2024) When Copilot Becomes Autopilot: Generative AI’s Critical Risk to Knowledge Work and a Critical Solution Sarkar_2024_GenAI_critical_v1.01.pdf

The Toolkit

Outlines seven key pillars of activity that institutions should take to address the challenges of generative AI and leverage its opportunities.

Guides institutions on ways to develop and implement these activities, augmented by institutional case-studies drawn from our partners.

Helps university staff to understand the benefits and disbenefits of generative AI to assist in their own work and effectively support students’ learning.

Supports academic educators to embed critical engagement with generative AI into their curricula through adaptions to their learning, teaching and assessment practices.

Supports students to critically engage with generative AI to support their learning.

Builds a bank of case-studies from a variety of disciplinary contexts which showcase how generative AI has been embedded in academic curricula and learning, teaching and assessment practices.

Figure 1: Seven Activity Pillars - Opportunities Based Framework

Pillars of the toolkit

To fully leverage the benefits of generative AI, without undermining any aspect of their mission, higher education institutions should develop strategic approaches to generative AI that connect across existing academic, educational and corporate policies and plans. Currently, many universities are taking a piecemeal approach to embedding generative AI across their academic, corporate and professional functions without due consideration to coherently addressing the seven challenges outlined in this project.

Key considerations

- Leverage expertise across the university in the development of your strategic approach to generative AI. Developments in artificial intelligence, more broadly, have a long history in higher education in both academic and professional services spaces e.g., in the academic discipline of Computer Science or using predicative analytics to address issues of student (dis)engagement and performance. See case-study 4.

- Connect current institutional initiatives around generative AI to each other and to your institution’s strategic goals and mission statement. See case-study 1.

- Balance using generative AI to maximise productivity and efficiency with adherence to the institution’s principles and polices on ethics, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) and environmental sustainability See case-study 7.

- Seek to embed appropriate AI statements in the policies and guidance of the University’s multiple functions including research, knowledge exchange and learning and teaching and assessment, as well as corporate functions (Information Technology, Human Resources, Finance, Communications, Planning and Data etc).

- Acknowledge and address inevitable tensions between ethical generative AI use in the various institutional functions e.g., between (educational) innovation and data security.

Strategic decisions about the use of generative AI in higher education should take account of a range of different perspectives to ensure effective engagement.

These perspectives should include institutional financial and digital infrastructure matters, academic and educational considerations as well as staffing and resourcing.

However, they should also consider ‘big picture’ issues around the use of generative AI such as the global challenges of social equity and justice, sustainability and its ethical use.

Creating a cross-institutional generative AI 'special interest' or 'community of practice' will support the effective development of pillar 1, if the group is used effectively as a key stakeholder group to inform the strategic direction of AI policy.

It can also serve to support the capacity building across key stakeholder groups and facilitate the sharing of good practice across, and between, academic units and professional services.

Key considerations

Be inclusive and consider an open invite to all colleagues. See Case-study 3; Case-study 5.

Reach out and invite key experts in AI either as participants or speakers, such as computer scientists in AI. They will be using AI technology to support their students in ways that could be developed and subsequently applied across the University for the benefit of all students. See Case-study 4; See Case-study 6.

Engage the expertise of educational developers responsible for guiding academic staff and IT and information specialists. See case-study 6.

Ensure that the group’s collective knowledge and learning is leveraged and fed into the development of institutional policy and strategy (pillar 1).

Encourage the exploration of a wide range of AI enabled/ driven technologies to support learning, administrative efficiencies, data analytics and enhanced service delivery. See case-study 8.

Encourage students to join, including their representative bodies. See Case-studies 5, 9 and 11.

Meet regularly given the speed in developments of AI.

Share practice across institutions and the sector. See case-study 2.

The availability of institutional licenses for AI tools and technologies is an essential step in facilitating the recalibration of educational activities to deliver graduates with the skills to address future global challenges.

It is paramount that universities provide access to AI tools where data and privacy are protected, allowing students to use AI tools safely and ethically to develop their skills and knowledge and successfully complete assignments requiring AI engagement to the highest level. Institutionally licensed tools also go some way to mitigating the digital divide where students have variable access to digital technologies due to personal financial circumstances.

However, generative AI tools are evolving at pace, with access rights and functionality continually changing. New tools are being released daily, pilot access to more powerful tools is being granted for limited periods of time, and new higher level subscription tiers are being introduced with their own benefits.

At the same time, Terms and Conditions and privacy policies vary considerably with attendant changes to privacy, copyright and identity. Given these challenges, it is beneficial for universities to diversity their range of generative AI tools with different providers, including developing pilots with bespoke education-focused technologies.

Key considerations

Universities must ensure that all staff and students have access to licensed generative AI tools and technologies.

Staff should be supported to understand and use these technologies in line with institutional AI policy and their effectiveness evaluated (see pillar 6).

All learning, teaching and assessment activities which require students to engage with generative AI must be achievable to the highest standard with the use of institutionally licensed tools.

Students (and staff) must not be required to create accounts on AI systems where there is no contractual agreement with the supplier.

Generative AI has the potential to negatively extend the digital divide which must be mitigated against.

Understanding that this field is evolving rapidly, and even with licensed tools, functionality and capabilities can change during an academic year. See case-study 7.

Continually test new generative AI enabled technologies to assess value and impact. See case-study 8.

Assessment security is central to the integrity of university degrees and has been a key focus in our project. Generative AI presents challenges to assessment validity and academic integrity. The ability of generative AI tools to create different forms of written work including reports, essays and reflective writing, as well as graphics and videos means that many conventional types of assessments present a low barrier to misuse.

There is no single form of assessment that enables students to demonstrate achievement of all learning outcomes, so our universities are looking at deploying a range of assessment methods which, together, can secure an award’s integrity.

Universities should review their assessment and academic integrity polices in the light of generative AI. Early on, all our universities grappled with how to apply existing misconduct definitions to situations involving generative AI, altering their definitions of plagiarism and/ or ‘commissioning to include AI generated work.

The principles of good assessment design should be leveraged to address the challenges of generative AI. Some institutional partners have taken the opportunity that generative AI has created to ‘go back to basics’, encouraging staff to reflect on the constructive alignment between assessments and learning outcomes and adopt approaches such as backward design.

Activities have also included emphasizing authentic learning and real-world applications and focusing on assignments that assess the ‘process’ of completing the assessment, rather than the product itself.

Our institutions have also adopted various approaches to detection, recognizing and working with the well-documented limitations and biases.

Key considerations

Ensure that the misuse of generative AI is addressed in academic integrity polices and regulations. See Case-study 9.

Review all assessment to ascertain their validity in an AI enabled world.

Take a course approach to review assessment, looking across levels to ensure coherence and diversity in the assessment diet. See Case-study 13.

Consider a risk-based approach to assessment transformation, prioritising changing high stakes, heavily weighted key assessments. See Case-study 13.

Develop an assessment framework where assessments are categorised with respect to how generative AI is allowed. See Case-study 12.

Consider including an assessment category where engagement with generative AI is required by the assessment, in order to assess students’ ability to recognise and minimise the limitations of generative AI, along with the development of their critical thinking skills and evaluative judgement. See Case-study 10.

Consider if it is appropriate to include a category of no AI use where the assessment is not conducted under controlled conditions or is not dialogic. See Case-study 10.

Require students to be transparent about their use of generative AI in their assessments.

Accelerate work with students on the principles of academic integrity, focusing on how generative AI tools re-present information developed by others, and, therefore, carry an inherent risk of plagiarised content and copyright infringement. (Pillar 7).

Ensure staff are supported to make appropriate decisions on the ‘inappropriate’ use of generative AI as academic misconduct. (Pillar 6). See Case-study 11.

Reduce the incentive for students to resort to the inappropriate use of AI by reviewing for example, tight deadlines and submission date clustering.

Consider carefully detection technologies, and their limitations such as false positives and ease of evasion, taking account of how it may pick up students with limited generative AI skills, rather than students who are more skilled in disguising AI generated content. See Case-study 11.

Alongside the review of assessment, generative AI provides an opportunity for institutions to reflect on and rethink their curricula content and learning and teaching practices to ensure that ‘what’ is being taught and ‘how’ it is being delivered is ‘fit for purpose’ in a generative AI enabled world.

This will include integrating consideration of the impact of AI technologies in different disciplinary contexts and the development of students’ AI literacies into the curricula – including how to use generative AI ethically, critically and with transparency.

Generative AI also provides significant incentive to adopt different learning and teaching strategies which diversify students’ skills sets beyond academic writing to support the assessment strategies needed to mitigate generative AI misuse.

Developing more authentic assessment (live-briefs, hackathons etc.) will require a focus on active pedagogies and provides an additional incentive (if one is needed) to move away from traditional forms of teaching in higher education such as the didactic lecture and encourage more team working and collaboration.

Active classroom pedagogies support the development of higher graduate skills. For example, oracy and dialogic learning and teaching could become more commonplace in higher education classrooms, ensuring that students practice their oracy skills of speaking and listening, and developing the confidence to complete and excel in dialogic-led activities and assessment.

Key considerations

Review curriculum content to integrate / address generative AI within the disciplinary context. See case-studies 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

Realign learning and teaching practice with new approaches to assessment and the development of higher skills. See case-studies 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

Consult stakeholders, including employers in your sector, to identify how they are embedding generative into their working practices in order to support students to develop discipline-appropriate AI literacies.

Provide students with opportunities to navigate an AI enabled future by embedding AI literacies into the curriculum. See case-studies 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

Educate students on the limitations of generative AI and how it creates content that is biased, inaccurate, out of date or in some cases completely fabricated (see case-study 26)

Engage with students in class on the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of generative AI misuse, strengthening their ability to navigate its use with greater judgement and integrity. See case-studies 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

One key activity that is pivotal to ensuring that students develop a critical, ethical and reflective approach to the use of generative AI tools is to engage educators in debates and support them to understand and use generative AI effectively and appropriately – both in their own work and in their approach to their learning, teaching and assessment.

Faculty educators have expressed varying attitudes toward AI. Many colleagues have already fully embraced generative AI as a pedagogical tool, while some in resistant to its adoption for various reasons including deep-seated concerns around its (un)ethical use, job displacement, and academic integrity.

Not only does this reiterate the need to actively involve educators in AI decision making processes, but also to ensure robust and regular support sessions which ensure that educators know and understand what Generative AI is, and what it isn’t, what it can and cannot do.

Both academic and professional staff should be supported to fully understand the implications of generative AI in order to develop the collective capability to harness the potential of generative AI. However, this should be achieved in the context of the academic mission of universities with an emphasis on safeguarding ethical practice, academic integrity, data privacy, intellectual property, equity and sustainability.

Key considerations

Ensure the clear communication of the institution’s generative AI policy, which outlines the rationale for the approach taken. See case-study 24.

Involve staff in the continued development of your institution’s generative AI policy and guidance documentation (see pillar 2). See Case-studies 2, 3 and 5.

Develop a holistic strategy to close the knowledge gap between innovators and other university staff – do not expect early adopters to be responsible for developing all staff in their disciplinary/ functional areas See case-study 21.

Provide training for staff on how generative AI works and how it is evolving, focusing staff minds tools on the fact that they are built on advanced pattern recognition capabilities, that are not intelligence in the human sense. See case-study 23.

Create resources for staff to work through in their own time – assuming no or limited knowledge of Large Language Models. See case-study 23; Case-study 25.

Provide training that is disciplinary specific. See case-study 22.

Adapt existing academic staff development mechanisms to support staff to review their curriculum and assessment in the context of generative AI and your institutional generative AI policies (see case-study 14).

Align this work with a broader focus on digital upskilling incentivising this with badges and the opportunity to gain generative AI qualifications. See case-study 23.

Engage students in the creation of generative AI resources to support staff. See Case-study 21.

Check in with staff regularly. What do staff need to be able to use it effectively, what are their barriers?

Generative AI is reshaping how students live and learn. They are routinely using generative AI tools to support them to achieve. In our project, students cited significant benefits of using generative AI, including improved productivity, clearer understanding of complex topics, and stronger writing skills.

Generative AI is fast becoming the ‘norm tech’ in their everyday lives, used to draft correspondence (from job application covering letters to eulogies), summarise key information and create or manipulate images.

Students are also using generative AI to support their academic studies including for proofreading and vocabulary support, as well as for summarising papers, structuring essays, brainstorming ideas, and clarifying complex topics. Generative AI has quickly become a study and revision companion, generating flashcards, exam questions, and quizzes to support their learning.

Students in creative fields are using generative AI for digital art, animation, and illustration: from recolouring to scriptwriting, whilst Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) students are using it to support coding, debugging and solving equations.

Our project highlights a range of levels of awareness of how Large Language Models (LLMs) work and some misunderstandings about how ‘intelligent’ these systems are (or are not). Whilst some students are very well informed about the limitations and raised legitimate concerns about ethical and privacy issues, academic integrity, and the environmental impact, others were less knowledgeable.

Disciplinary differences were noted with students studying in creative fields, being particularly well informed, concerned specifically about originality, copyright, and future job prospects.

However, a universal concern cited by students was unclear university guidance, with many finding policies vague or inconsistent, which caused significant confusion and anxiety. Students also noted a wide range of knowledge and understanding of generative AI amongst their academic teachers.

Key considerations

Ensure that the University’s approach to generative AI is visible from welcome week by showcasing it on plasma screens, events at welcome fayres and by updating student welcome emails, handbooks and other relevant information sources.

Create simple, but memorable logos to support your institutional approach and create merchandise to give to students. See Case-study 24.

Update your academic integrity module to inform new and continuing students about the institutional policy on generative AI – and monitor its uptake. Consider making engagement mandatory.

Provide training for students, considering aligning training with staff and students. See Case-study 25; Case-study 26.

Consider creating a student-facing training module (with mandatory completion if possible) to increase student AI and digital literacies.

Gather regular feedback from students on how they are using generative AI and on how policies are being interpreted and the kinds of misconceptions which are circulating. See Case-study 24.

Ensure that students have a voice in the co-creation of generative AI strategies and how this is communicated. See Case-study 21.

Provide students with opportunities to navigate an AI enabled future by embedding AI literacies into the curriculum (Pillar 5).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our collaborators and contributors:

Anglia Ruskin University: Dr Alexander Moseley

Kingston University: Dr Annie Hughes, Dr Tim Linsey, Valentina Scarinzi, Dr Darrel Greenhill, Dr Owen Spendiff and Wayne Leung

Leeds Beckett University: Lee Jones, Rebecca Sellers, Helen Howard, Erin Nephin, Rianne MacArthur and Tom Hey

Robert Gordon University: Dr Rachel McGregor, Dr Mark Zarb and Dr Elliot Pirie

University of Birmingham: Dr Marcus Perlman, Professor Daniel Moore and academic staff in the School of English, Drama and Creative Studies

University of Brighton: Juliet Eve, Dr Alison Willows, Dr Sarah Stevens, Marcus Winter and Dao Tunprasert

University of Greenwich: Dr Gerhard Kristandl

University of Hertfordshire: Professor Sarah Flynn, Catherine Rendell, Mary Martala-Lockett, Mark Holloway and Saint John Walker

University of Westminster: Dr Mazia Yassim, Professor Gunter Saunders and Dr Doug Specht

University of the West of England: Charlotte Evans and Mark Shand