27 July 2022

Active Online Reading – findings and recommendations

Author

Jamie Wood

Professor of History and Education, School of History and Heritage, University of Lincoln

For the past year or so, I have been coordinating Active Online Reading, a Collaborative Enhancement project on how students learn online and how we teach them to do so in higher education in the UK. We’ve just published the final report, which gives the full story of the project – what we and the students we worked with did and what we learned from doing so. In this post, I want to share some of our key findings and recommendations. If you’d like to know more, I encourage you to read the full report. If you’d like to get involved, drop us a line because one thing is for sure – there is a lot of work to do in this area!

I’d like to begin with a caveat. Reading cannot be treated separately from other skills – most obviously, writing, but others too, such as information literacy and the disposition towards ‘independence’, as well as the whole package of capabilities encompassed by ‘research’. Reading is a – perhaps the – core skill, but it cannot be treated alone. Similarly, reading in online spaces cannot easily be distinguished from reading in other contexts (‘offline’ or ‘analogue’). We found that, for example, many students, for a variety of reasons, find it very difficult – and often physically painful – to read online and so prefer to print them off even if they have easy access to digital versions. What does that mean in a context in which readings are increasingly provided to students in digital formats via a plethora of online platforms?

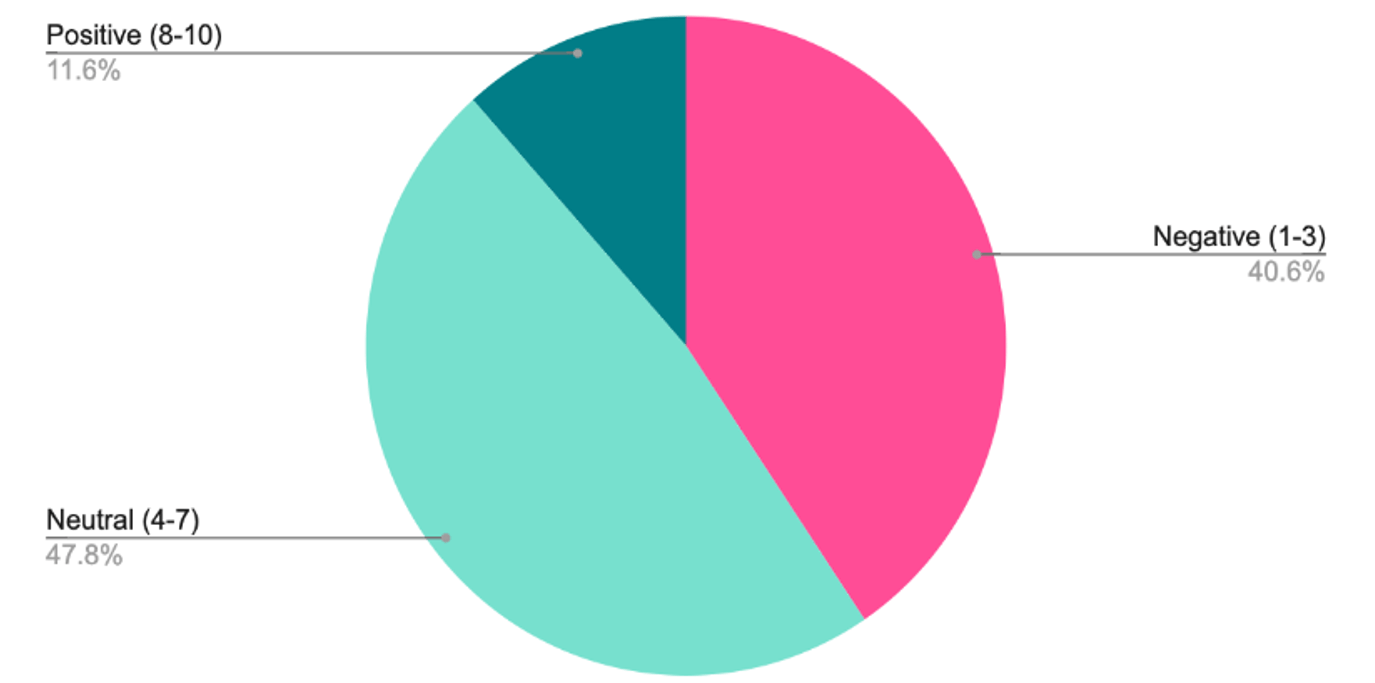

Moving on to our findings. Among staff, we observed a widespread deficit understanding of student reading. Staff rated their students’ reading skills for academic study rather poorly indeed, as the following graph illustrates.

Qualitative responses to our staff survey also suggest that academics think that, in general, students’ reading skills are not particularly well developed.

I outline the set reading for the following week at the end of the seminar, and email again midway through the week to remind them. For broader, curiosity-driven reading outside of summative assessments, I confess I don't see much evidence.’ (UK academic)

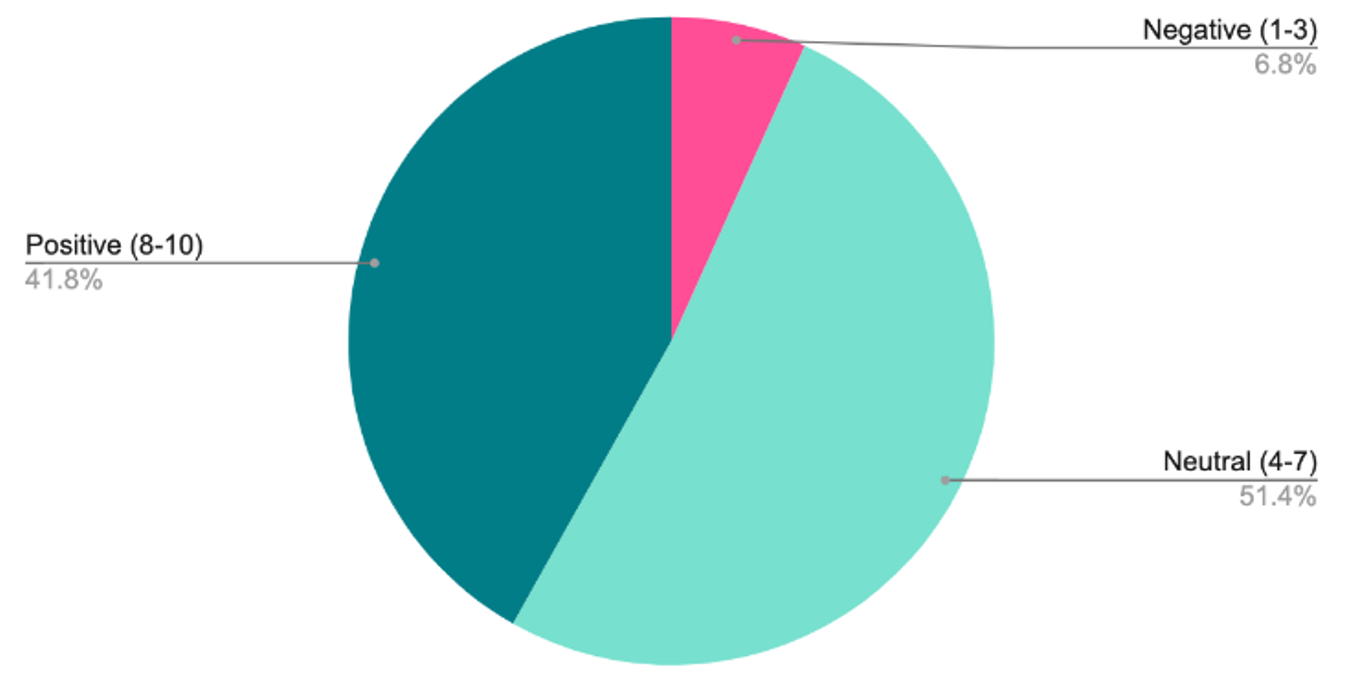

Students rated their academic reading skills much more positively than their lecturers.

This disjunction between academic staff and students is concerning because it suggests that there is a lack of understanding on both sides. Work needs to be done not just to develop students reading habits (to address the gap that academics identify) but also to encourage them to adjust their perceptions and recognise that reading at university may require a different approach to those they have deployed before.

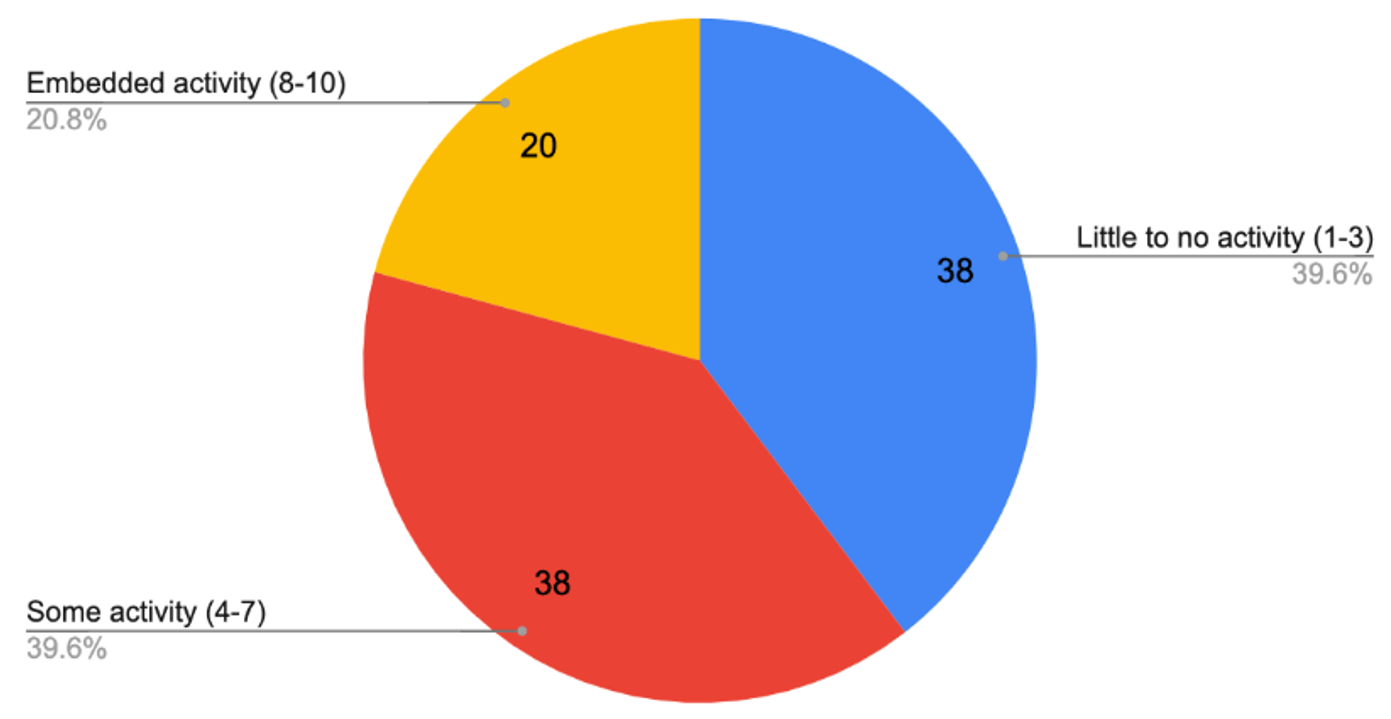

Staff have work to do too, if they are to meet students halfway, ‘where they are’ (in the real world) rather than where we collectively wish they would be. Despite the overwhelming majority of staff rating online reading as indispensable for study in their discipline and the aforementioned lack of student skill in reading in general, not many academics pay much attention to cultivating online reading skills in their modules.

Some work therefore needs to be done to encourage staff to adjust their expectations and develop pedagogies in this area. While we identified some really innovative work in the course of the project and have shared much of it on our website, it is noteworthy that when we asked academics to explain how they taught students to read online, the most popular response related to the selection of the text (length and ‘appropriateness’, for instance), while the most frequently mentioned pedagogic strategy was didactic in focus (‘telling’ students how to read). For us, these trends didn’t reflect a particularly developed pedagogy for teaching reading – online or not.

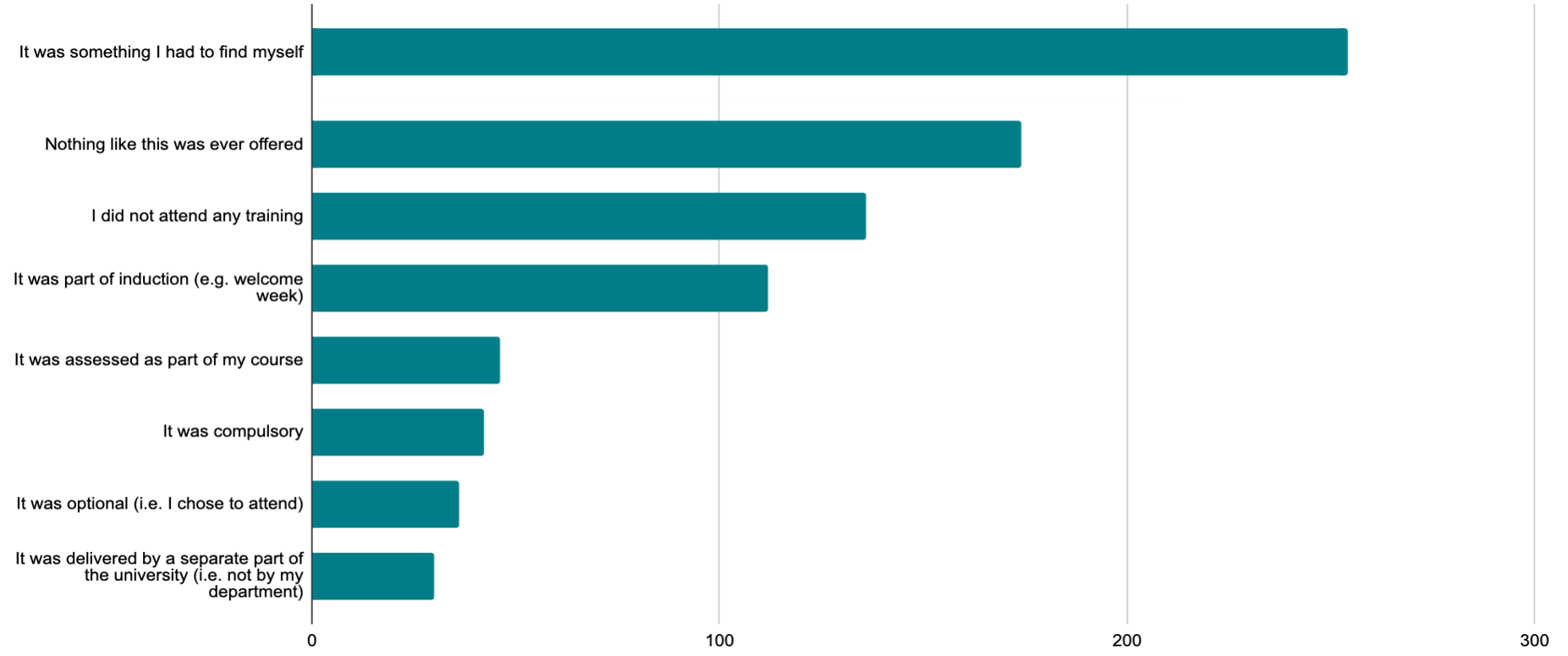

Finally, there are issues relating to the timing of reading development activities. Many students and staff talked about instruction in reading at university level taking place early in the course, often during induction. While some students spoke about the usefulness of these sessions, in general this approach does not seem to have been particularly successful engaging a wide range of students.

Figure 4: Student responses to a question on the sorts of support that was available for supporting their reading skills development - click image to view a larger size

Indeed, given that one of the key issues identified above is a need to encourage students to adjust their expectations about reading in higher education, a more structured approach seems to be in order, especially in relation to online reading. If training in university-level reading is to become more than a box-ticking exercise, a stepped approach that embeds reading development work across curricula and addresses progression between levels could prove fruitful.

In recent weeks I have begun to think that we need to think about how the transition to university-level study is akin to learning a new language at the same time as they are being asked to play an unfamiliar game. If we are to enable students to succeed in this new context, we need to think more deeply about how we can enable them to learn that language to enable them to play the game. Otherwise, we are setting them up to fail. Thankfully, there is lots of good work going on in this area and we encourage you to check out our project to learn a little bit about how to address some of these challenges.