17 July 2025

Is ‘constructive disalignment’ undermining Higher Education for everyone?

This article from the University of Hull’s Collaborative Enhancement Project explores how ‘constructive disalignment’ - a mismatch between curriculum design and stakeholder needs - may be contributing to growing dissatisfaction with UK Higher Education. It introduces the concept of ‘authentic alignment’, calling for data-informed, competence-based curricula that better reflect the expectations of students, employers and society.

Authors

Dr Andrew Holmes

University of Hull

Dr Dom Henri

University of Hull

There is considerable evidence of growing dissatisfaction with Higher Education in the UK. For example, approximately half of 2,024 graduates surveyed in 2024, would have made different choices about when, where or what they chose to study (Dandridge et al., 2025); with career opportunities being a significant factor in this.

Similarly, we are seeing increasing questioning of the role of universities in raising and enabling aspirational student futures and calls for complete transformation of the ‘traditional’ model of Higher Education (see The fall in graduate salaries shows the argument for mass entry to higher education has failed; The Graduate Premium: manna, myth or plain mis-selling? and Universities should be architects of economic and social transformation).

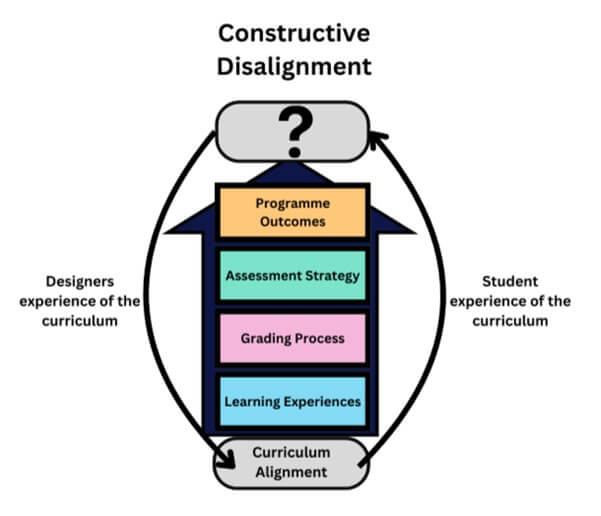

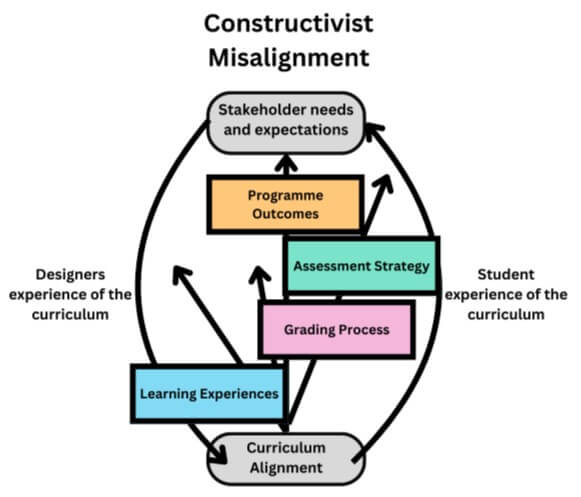

We suggest that the growing sense of dissatisfaction among students, employers and society is at least partially result of ‘constructive disalignment’, which is ‘what occurs when any element of a programme’s educational experience is not aligned with the needs and expectations of its stakeholders (students and society)’

Our diagram below shows the difference between constructive disalignment and the more commonly used term curriculum ‘misalignment’. Disalignment focuses particularly on what the curriculum is trying to achieve, and misalignment is how well the curriculum facilitates the achievement of its purpose. We specifically include the term ‘constructive’, to highlight the common misinterpretation of the original theory, which proposed a collaborative approach to curriculum construction, not purely an educator-led one (Biggs, 1995).

A quick consideration of ‘Constructive Alignment’

John Biggs’ (1996) concept of ‘constructive alignment’ is an educational theory that has had a highly significant impact on Higher Education; most commonly in the adoption of ‘learning outcomes’ based programme design. The original theory had two key facets:

Firstly, that a programme of study should be designed to teach and assess outcomes that determine the purpose of that programme; i.e. educational methods are aligned to educational goals.

Secondly, that the pedagogical philosophy underpinning a curriculum should be one of constructivism. Acknowledging that learners do not passively absorb information, but instead actively construct their knowledge and understanding based on prior learning, interactions with their environment and others, and reflection.

However, there has been criticism, not of the model, but that the term constructive alignment has been, in effect, hijacked to support top-down institutional, management and regulatory processes, rather than effective teaching and learning. For an in-depth discussion of this, along with a history of constructive alignment and how constructivism ‘disappeared’ from the theory as it was implemented in HE see Loughlin, Lygo-Bakear and Lindberg-Sand (2020).

We believe that the loss of constructivism from the curriculum development process is particularly problematic because of the increasing consumerisation of Higher Education. Students come to university with expectations of what a degree will, or will not, mean for them and their future; which shapes their engagement and satisfaction with their education. Evidence suggests that, as a sector, we have limited understanding of individual student expectations and needs, without which we have struggled to meet them (Balloo, 2018; Bunce Baird, and Jones, 2017 CIPD, 2022; Dandridge et al., 2025). The lack of understanding of our students and the stakeholders that will define their future success (e.g. employers) is a root cause of constructive disalignment.

So, do we have any evidence of the widespread presence of ‘constructive disalignment’ in higher education?

Example: Critical thinking pedagogies that do not develop critical skills for employment or citizenship (the case for many other transferable skills).

Transferring critical thinking skills to non-academic contexts requires pedagogies that actively facilitate this transfer (van Peppen et al., 2020). Curricula need to help students apply critical reasoning in authentic contexts, or they won’t be able to apply their learning to their personal and professional futures. In our experience, interdisciplinary real-world problem solving is a fringe Higher Education activity not a core component of most degrees in need if greater development. Which is probably why there is limited evidence that university education improves ‘critical reasoning’ and persistent evidence of critical thinking related skills gaps (Arum & Roska, 2011).

A mismatch between graduate competencies and employer needs is repeated across industry-led reports produced for specific sectors, including the life sciences (SIP, 2022), the bioeconomy (Peasland et al., 2022), engineering (EngineeringUK, 2023), and the Further Education sector (NCFE, 2023). Findings repeatedly raise concerns around students’ professional attitudes, resilience, interpersonal skills, digital literacy, and interdisciplinary thinking (see, for example, Webb and Chaffer, 2016). In short, multiple stakeholders are increasingly questioning whether university curricula are optimised to achieve what those stakeholders need and expect it to.

‘Authentic Alignment’

The C-BAss framework is designed to achieve ‘authentic’ alignment’. Authentic because the programme outcomes are built on a detailed understanding of stakeholders and their expectations, needs and wants. We believe the focal stakeholder is the student, who is both the primary funder of the current university sector and key determinant of whether their degree will be successful in achieving its purpose (Khan & Hemsley-Brown, 2024). However, the perspectives of other stakeholders are essential for designing curricula that can achieve its outcomes most effectively; e.g. local communities, employers, the government, the Quality Assurance Agency, PSRBs, etc.

Question to consider

To what extent is your curriculum built on a deep, data-driven understanding of your students aspirations, expectations and past experiences?

References

- Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2011). Academically adrift: Limited learning on college campuses. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Balloo, K., 2018. In-depth profiles of the expectations of undergraduate students commencing university: a Q methodological analysis. Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), pp.2251-2262.

- Bunce, L., Baird, A. and Jones, S.E., 2017. The student-as-consumer approach in higher education and its effects on academic performance. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), pp.1958-1978.

- Calma, A. and Davies, M., 2025. Assessing students’ critical thinking abilities via a systematic evaluation of essays. Studies in Higher Education, pp.1-16.

- CIPD. (2022) What is the scale and impact of graduate overqualification in the UK? London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

- Danczak, S.M., Thompson, C.D. and Overton, T.L., 2017. ‘What does the term Critical Thinking mean to you?’A qualitative analysis of chemistry undergraduate, teaching staff and employers' views of critical thinking. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 18(3), pp.420-434.

- Dandridge, N. Huang, YH.I., Casoni, V.P. and Watermeyer, R. (2025). The Benefits of Hindsight: Reconsidering higher education choices. AdvanceHE and HEPI.

- Employer Skills Survey [ESS] (2022). https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/employer-skills-survey/2022 (Accessed 11/10/2024).

- Ennis, R.H., 2015. Critical thinking: A streamlined conception. In The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education (pp. 31-47). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- EngineeringUK. (2023). Engineering Skills Needs. Available at: https://www.engineeringuk.com/research-and-insights/our-research-reports/engineering-skills-needs-now-and-into-the-future/ (Accessed: 25 November 2024).

- Employer Skills Survey https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/employer-skills-survey-2022

- Khan, J. and Hemsley-Brown, J., 2024. Student satisfaction: The role of expectations in mitigating the pain of paying fees. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 34(1), pp.178-200.

- Loughlin, C., Lygo-Baker, S., & Lindberg-Sand, Å. (2020). Reclaiming constructive alignment. European Journal of Higher Education, 11(2), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2020.1816197

- NCFE (2023). NCFE 175TH ANNIVERSARY Sector Spotlight: Further Education. Available at: https://www.ncfe.org.uk/all-articles/addressing-increasing-skills-gaps-fe/ (Accessed: 15 November 2024).

- Pearl, A.O., Rayner, G.M., Larson, I. and Orlando, L., 2019. Thinking about critical thinking: An industry perspective. Industry and Higher Education, 33(2), pp.116-126.

- Peasland, E., Scott, G., Hubbard, K., Henri, D., and Morrell, L. ‘THYME: strengthening the Bioeconomy by maximising graduate employability’. Available at: https://www.hull.ac.uk/work-with-us/research/institutes/energy-and-environment-institute/docs/thyme-bioeconomy-by-maximising-graduate-employability-extended-report.pdf (Accessed: 15 November 2024)

- van Peppen, L. M., van Gog, T., Verkoeijen, P.P.J.L., and Alexander, P. A. (2021) Identifying obstacles to transfer of critical thinking skills. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 34(2), pp.261–288. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2021.1990302

- Webb, J. and Chaffer, C. (2016) The expectation performance gap in accounting education: a review of generic skills development in UK accounting degrees. Accounting Education, 25(4), pp.349-367. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2016.1191274